George W. Johnson, the First Black Recording Star

(And what would he have thought about seeing himself on the Internet?)

(Click here for Audio Samples)

(Click here for Biography)

(Click here for Additional Resources)

(Click here for Acknowledgments and Notes)

Audio Samples

An unidentified early 1890s cylinder of “The Whistling Coon”

1905 Edison cylinder 4004 of “The Laughing Song,” with orchestra accompaniment

Biographical Sketch of George W. Johnson (1846-1914)

The First Black Recording Star

by Tim Brooks

George Washington Johnson is one of the most fascinating unsung heroes in recording history. Possibly the first African-American to record, and certainly the first to become widely successful as a recording artist (in the 1890s), he has been virtually ignored in the history books. In part this is because writers just don’t know about him, and in part because of embarrassment about the songs he sang. The first successful black recording artist was, after all, billed as “The Whistling Coon”, “coon” being a derogatory term for blacks.

George Washington Johnson is one of the most fascinating unsung heroes in recording history. Possibly the first African-American to record, and certainly the first to become widely successful as a recording artist (in the 1890s), he has been virtually ignored in the history books. In part this is because writers just don’t know about him, and in part because of embarrassment about the songs he sang. The first successful black recording artist was, after all, billed as “The Whistling Coon”, “coon” being a derogatory term for blacks.

![]() Whatever compromises Johnson had to make in order to be heard in those racially oppressive times, he showed that it was possible for a black man to sell a lot of records to white America, opening doors for those who would come later with less offensive material. He was also very well liked in the industry, a friendly, hard working older man who though treated unkindly by life (born a slave, forced to endure the many indignities visited upon African-Americans in the post-Civil War era) nevertheless built a substantial career in the young industry while making many friends among white artists and phonograph entrepreneurs. They stood by him in his time of need, coming to his aid when he was accused of murder in 1899.

Whatever compromises Johnson had to make in order to be heard in those racially oppressive times, he showed that it was possible for a black man to sell a lot of records to white America, opening doors for those who would come later with less offensive material. He was also very well liked in the industry, a friendly, hard working older man who though treated unkindly by life (born a slave, forced to endure the many indignities visited upon African-Americans in the post-Civil War era) nevertheless built a substantial career in the young industry while making many friends among white artists and phonograph entrepreneurs. They stood by him in his time of need, coming to his aid when he was accused of murder in 1899.

![]() The most comprehensive account of Johnson’s colorful life and career is contained in the first three chapters of my book Lost Sounds. Following is an abbreviated summary.

The most comprehensive account of Johnson’s colorful life and career is contained in the first three chapters of my book Lost Sounds. Following is an abbreviated summary.

![]() Johnson was probably born in or near Wheatland, in Loudoun County, Virginia, a rural area about 30 miles northwest of Washington, D.C., in mid October, 1846. His exact date of birth will never be known with certainty, and it is likely he didn’t know it himself. There were no birth certificates for slave children and Johnson’s parents were most likely two illiterate teenage slaves, Samuel (15) and Druanna (13). His “family” (he may have had some siblings) was never mentioned in later years, and they disappeared from census records after 1860.

Johnson was probably born in or near Wheatland, in Loudoun County, Virginia, a rural area about 30 miles northwest of Washington, D.C., in mid October, 1846. His exact date of birth will never be known with certainty, and it is likely he didn’t know it himself. There were no birth certificates for slave children and Johnson’s parents were most likely two illiterate teenage slaves, Samuel (15) and Druanna (13). His “family” (he may have had some siblings) was never mentioned in later years, and they disappeared from census records after 1860.

![]() Young George was lucky in some respects, however. As an infant he was taken in by a prosperous white family named the Moores who made him the “bodyservant” (i.e. playmate) of their newborn son Sam. The Moores ran a large, bustling farm called Glenmore, and George spent his early years in their big home learning how to get along in white society, about music (he sat in on Sam Moore’s music lessons) and even to read and write. It was illegal to teach slaves to read and write in antebellum Virginia, but Johnson soon had those essential skills.

Young George was lucky in some respects, however. As an infant he was taken in by a prosperous white family named the Moores who made him the “bodyservant” (i.e. playmate) of their newborn son Sam. The Moores ran a large, bustling farm called Glenmore, and George spent his early years in their big home learning how to get along in white society, about music (he sat in on Sam Moore’s music lessons) and even to read and write. It was illegal to teach slaves to read and write in antebellum Virginia, but Johnson soon had those essential skills.

![]() This peaceful world was soon destroyed by the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861. Some of the greatest battles of the war took place in and around Loudoun County, and by the end of the war its economy had been almost totally destroyed. George’s white friend Sam served in the Confederate Army during the late years of the war, and one of Sam’s brothers was killed near Fredericksburg. After the war ended George, now in his early twenties, worked as a laborer in the area for a few years, and may have been briefly employed as a schoolteacher. But there was no future for him in Virginia. Oppression of blacks through Jim Crow laws and the tenant farming system (slavery under another name) was the norm during the post-war years.

This peaceful world was soon destroyed by the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861. Some of the greatest battles of the war took place in and around Loudoun County, and by the end of the war its economy had been almost totally destroyed. George’s white friend Sam served in the Confederate Army during the late years of the war, and one of Sam’s brothers was killed near Fredericksburg. After the war ended George, now in his early twenties, worked as a laborer in the area for a few years, and may have been briefly employed as a schoolteacher. But there was no future for him in Virginia. Oppression of blacks through Jim Crow laws and the tenant farming system (slavery under another name) was the norm during the post-war years.

![]() Sometime during the 1870s, probably in either 1873 or 1876, Johnson “went North” to New York City to try to carve out a new life. He had become an expert whistler, and also had a talent for “laughing songs,” odd little ditties in which he laughed in time with the music. With his broad smile, hearty laugh and willingness to mock himself, white audiences found him quite appealing. He slowly developed a small scale musical career in New York, while living in the Hell’s Kitchen slums of Manhattan’s west side. Upper class whites (including future Vice President of the U.S. Levi P. Morton) sometimes hired him for entertainments, and he may have had a brief stint touring with the well known Georgia Minstrels. Most of his time was spent busking on the streets of New York and in ferry terminals and other public places, singing and whistling for coins. Johnson became a familiar New York “street character.” There is some evidence that he may have been recruited to make tinfoil recordings when Thomas Edison’s newly invented phonograph was first exhibited to the public in 1878 and 1879.

Sometime during the 1870s, probably in either 1873 or 1876, Johnson “went North” to New York City to try to carve out a new life. He had become an expert whistler, and also had a talent for “laughing songs,” odd little ditties in which he laughed in time with the music. With his broad smile, hearty laugh and willingness to mock himself, white audiences found him quite appealing. He slowly developed a small scale musical career in New York, while living in the Hell’s Kitchen slums of Manhattan’s west side. Upper class whites (including future Vice President of the U.S. Levi P. Morton) sometimes hired him for entertainments, and he may have had a brief stint touring with the well known Georgia Minstrels. Most of his time was spent busking on the streets of New York and in ferry terminals and other public places, singing and whistling for coins. Johnson became a familiar New York “street character.” There is some evidence that he may have been recruited to make tinfoil recordings when Thomas Edison’s newly invented phonograph was first exhibited to the public in 1878 and 1879.

![]() By 1890 he was in his forties and just scraping by, picking up odd jobs and singing on the streets of New York, when his life was changed forever. Edison’s original tinfoil phonograph had been primitive and impractical for mass use, and could be operated only by experts. But it had finally been improved to the point that it could now be commercially exploited. Young entrepreneurs began to set up local dealerships to market it, under license from the patent-holding North American Phonograph Company. Since the public saw it as an entertainment device, they were soon looking for cheap “talent” to make musical cylinders. There were some “technical problems,” as the saying goes. There was no way to make duplicates of a wax cylinder so the singer had to perform the same song over and over again to build up enough stock to sell. Sometimes several recording machines could be grouped in front of the singer in order to yield three or four copies at a time, but that was about it. Also the sound was still not very clear, and recording required someone with a very strong voice and clear articulation.

By 1890 he was in his forties and just scraping by, picking up odd jobs and singing on the streets of New York, when his life was changed forever. Edison’s original tinfoil phonograph had been primitive and impractical for mass use, and could be operated only by experts. But it had finally been improved to the point that it could now be commercially exploited. Young entrepreneurs began to set up local dealerships to market it, under license from the patent-holding North American Phonograph Company. Since the public saw it as an entertainment device, they were soon looking for cheap “talent” to make musical cylinders. There were some “technical problems,” as the saying goes. There was no way to make duplicates of a wax cylinder so the singer had to perform the same song over and over again to build up enough stock to sell. Sometimes several recording machines could be grouped in front of the singer in order to yield three or four copies at a time, but that was about it. Also the sound was still not very clear, and recording required someone with a very strong voice and clear articulation.

![]() The friendly, middle aged black man who sang and whistled on the streets of New York was available, cheap and willing to work all afternoon. He had a strong pair of lungs and his whistling and laughter was as hearty at the end of the day as it had been at the beginning. Just what the entrepreneurs needed. Moreover he had two specialties that made listeners (at least white listeners) laugh. One was “The Whistling Coon,” a comic minstrel song written a decade earlier in which he whistled in time with the music; and the other, “The Laughing Song” in which he laughed along with the melody. Both made fun of blacks (“He’s got a pair of lips, like a pound of liver split, and a nose like an injun rubber shoe” “He’s an independent, free and easy, fat and greasy ham, with a cranium like a big baboon”), and the sight of a jovial black man indulging in such self-mockery was, to many, highly entertaining.

The friendly, middle aged black man who sang and whistled on the streets of New York was available, cheap and willing to work all afternoon. He had a strong pair of lungs and his whistling and laughter was as hearty at the end of the day as it had been at the beginning. Just what the entrepreneurs needed. Moreover he had two specialties that made listeners (at least white listeners) laugh. One was “The Whistling Coon,” a comic minstrel song written a decade earlier in which he whistled in time with the music; and the other, “The Laughing Song” in which he laughed along with the melody. Both made fun of blacks (“He’s got a pair of lips, like a pound of liver split, and a nose like an injun rubber shoe” “He’s an independent, free and easy, fat and greasy ham, with a cranium like a big baboon”), and the sight of a jovial black man indulging in such self-mockery was, to many, highly entertaining.

![]() Johnson first recorded his two specialties in the spring of 1890 for the Metropolitan Phonograph Company of New York, and slightly later that year for the New Jersey Phonograph Company of Newark. They were immediate hits. At the time cylinders were sold not to individuals but mainly to exhibitors, who took the still-expensive Edison phonograph on the road and demonstrated it in halls and town squares across the country. They also set up “phonograph parlors” with automatic machines, a kind of early jukebox. People listened through acoustical ear tubes rather than through an open horn, paying a small fee for the experience. This was how most Americans were introduced to the phonograph. Everyone wanted to hear the jovial records by the black man. The exhibitors kept wearing out copies and ordering more. Johnson was brought back to the studio again and again to produce more copies. Although he didn’t get royalties, he was paid by the session and began to make some very nice money from this sideline.

Johnson first recorded his two specialties in the spring of 1890 for the Metropolitan Phonograph Company of New York, and slightly later that year for the New Jersey Phonograph Company of Newark. They were immediate hits. At the time cylinders were sold not to individuals but mainly to exhibitors, who took the still-expensive Edison phonograph on the road and demonstrated it in halls and town squares across the country. They also set up “phonograph parlors” with automatic machines, a kind of early jukebox. People listened through acoustical ear tubes rather than through an open horn, paying a small fee for the experience. This was how most Americans were introduced to the phonograph. Everyone wanted to hear the jovial records by the black man. The exhibitors kept wearing out copies and ordering more. Johnson was brought back to the studio again and again to produce more copies. Although he didn’t get royalties, he was paid by the session and began to make some very nice money from this sideline.

![]() He also became widely known as the records were shipped across the country and even overseas. Edison invited him to his laboratory in West Orange, New Jersey, to record there, and other companies began pursuing him as well. Remarkably, as years passed, the records kept selling, becoming standards rather than transitory hits. By the late 1890s they were said to have sold over 50,000 copies, a phenomenal total considering the labor involved in producing that many, and the still-small scale of the industry. They are believed to be the best selling records of the entire decade of the 1890s.

He also became widely known as the records were shipped across the country and even overseas. Edison invited him to his laboratory in West Orange, New Jersey, to record there, and other companies began pursuing him as well. Remarkably, as years passed, the records kept selling, becoming standards rather than transitory hits. By the late 1890s they were said to have sold over 50,000 copies, a phenomenal total considering the labor involved in producing that many, and the still-small scale of the industry. They are believed to be the best selling records of the entire decade of the 1890s.

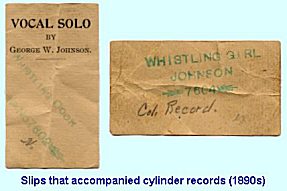

![]() In 1894 Johnson was invited by white friend and record producer Len Spencer to join him in making a series of “minstrel records,” short three or four minute recreations of a traditional minstrel show complete with an opening announcer (“Gentlemen, be seated”), introductory overture, jokes between the endmen, and a big closing song by the featured singer. Johnson’s role was to supply hearty laughter suggesting a live performance, and on some records sing his own “Laughing Song” as the closing number. The minstrel records were big hits, and provided another venue for his work continuing through the early 1900s. He also added some new songs to his repertoire, two of which, “The Laughing Coon” and “The Whistling Girl,” while not as wildly popular as the evergreen “Laughing Song” and “Whistling Coon,” did reasonably well. Others included “Listen to the Mocking Bird” and, a little later, the very obscure “Carving the Duck.”

In 1894 Johnson was invited by white friend and record producer Len Spencer to join him in making a series of “minstrel records,” short three or four minute recreations of a traditional minstrel show complete with an opening announcer (“Gentlemen, be seated”), introductory overture, jokes between the endmen, and a big closing song by the featured singer. Johnson’s role was to supply hearty laughter suggesting a live performance, and on some records sing his own “Laughing Song” as the closing number. The minstrel records were big hits, and provided another venue for his work continuing through the early 1900s. He also added some new songs to his repertoire, two of which, “The Laughing Coon” and “The Whistling Girl,” while not as wildly popular as the evergreen “Laughing Song” and “Whistling Coon,” did reasonably well. Others included “Listen to the Mocking Bird” and, a little later, the very obscure “Carving the Duck.”

![]() Johnson’s personal troubles began in the late 1890s. While not rich by any means he was making decent money now, but still living in the tenements of Hell’s Kitchen. This aroused jealousy, especially among Irish street cops (a black street person was suddenly making more money than they were). Adding fuel to the fire, he lived with light-skinned and possibly even white women. The women were lower class and itinerant, but black men were not supposed to mix with white women. In late 1894 or early 1895 a “German woman” with whom he was living died under mysterious circumstances, and Johnson was brought in for questioning but not charged. Then in 1896 he moved in with a mulatto woman named Roskin Stuart. He was nearly 50, she was about 35. He was very dark skinned, she was light. According to later testimony she was a real hell-raiser and he acted as something of a father figure to her. Their relationship was tumultuous. In 1898 she fell or was pushed out of a second story window, but survived and did not file a complaint. Later she tried to shoot him but missed, and they broke up, then got back together again. In the early morning of October 12, 1899, Johnson reported finding her beaten and unconscious in their spartan apartment after an apparent night of carousing; she died a few hours later.

Johnson’s personal troubles began in the late 1890s. While not rich by any means he was making decent money now, but still living in the tenements of Hell’s Kitchen. This aroused jealousy, especially among Irish street cops (a black street person was suddenly making more money than they were). Adding fuel to the fire, he lived with light-skinned and possibly even white women. The women were lower class and itinerant, but black men were not supposed to mix with white women. In late 1894 or early 1895 a “German woman” with whom he was living died under mysterious circumstances, and Johnson was brought in for questioning but not charged. Then in 1896 he moved in with a mulatto woman named Roskin Stuart. He was nearly 50, she was about 35. He was very dark skinned, she was light. According to later testimony she was a real hell-raiser and he acted as something of a father figure to her. Their relationship was tumultuous. In 1898 she fell or was pushed out of a second story window, but survived and did not file a complaint. Later she tried to shoot him but missed, and they broke up, then got back together again. In the early morning of October 12, 1899, Johnson reported finding her beaten and unconscious in their spartan apartment after an apparent night of carousing; she died a few hours later.

![]() Johnson was arrested and charged with murder. Numerous friends, black and white, rallied to his side. Character witnesses came forward to testify, including Sam Moore, now a successful businessman, who came all the way from Virginia to support his old friend. A collection was taken and two first-rate (white) defense lawyers were hired. When the trial opened on December 20, 1899, the courtroom was packed, with reporters from the major New York newspapers in attendance (“‘Whistling Coon’ on Trial” – New York Herald, New York World,New York Times).

Johnson was arrested and charged with murder. Numerous friends, black and white, rallied to his side. Character witnesses came forward to testify, including Sam Moore, now a successful businessman, who came all the way from Virginia to support his old friend. A collection was taken and two first-rate (white) defense lawyers were hired. When the trial opened on December 20, 1899, the courtroom was packed, with reporters from the major New York newspapers in attendance (“‘Whistling Coon’ on Trial” – New York Herald, New York World,New York Times).

![]() The prosecution’s case was entirely circumstantial and was a shambles. Its own witnesses spoke highly of Johnson and portrayed Stuart as out of control, the wrong morgue attendant was subpoenaed, neither the physician nor the coroner could testify as to the actual cause of death, and most importantly no one had seen anything. Finally after many objections and motions for dismissal by Johnson’s attorneys, the D.A. abandoned the case. Johnson never took the stand. He emerged on the steps of the courtroom to a cheering crowd (“Whistling Coon is Free” – New York Sun).

The prosecution’s case was entirely circumstantial and was a shambles. Its own witnesses spoke highly of Johnson and portrayed Stuart as out of control, the wrong morgue attendant was subpoenaed, neither the physician nor the coroner could testify as to the actual cause of death, and most importantly no one had seen anything. Finally after many objections and motions for dismissal by Johnson’s attorneys, the D.A. abandoned the case. Johnson never took the stand. He emerged on the steps of the courtroom to a cheering crowd (“Whistling Coon is Free” – New York Sun).

![]() He resumed his career without difficulty, but there were storm clouds on the horizon. All through the 1890s record companies had been working on ways to make duplicate copies, with some success, and by 1902 both disc and cylinder makers had developed methods to mass produce copies from a single original master recording. Johnson was recording his few specialties for all the major companies by this time, Victor (discs), Edison (cylinders) and Columbia (cylinders and discs), plus many minor labels. As soon as each of them had secured a suitable master recording from him they didn’t need him any more, and his income dropped precipitously. His friend Len Spencer got him work on minstrel and other novelty records, but after a dozen-year run “The Whistling Coon” was becoming yesterday’s news. In addition white artists began to successfully cover his recordings, especially the whistling numbers.

He resumed his career without difficulty, but there were storm clouds on the horizon. All through the 1890s record companies had been working on ways to make duplicate copies, with some success, and by 1902 both disc and cylinder makers had developed methods to mass produce copies from a single original master recording. Johnson was recording his few specialties for all the major companies by this time, Victor (discs), Edison (cylinders) and Columbia (cylinders and discs), plus many minor labels. As soon as each of them had secured a suitable master recording from him they didn’t need him any more, and his income dropped precipitously. His friend Len Spencer got him work on minstrel and other novelty records, but after a dozen-year run “The Whistling Coon” was becoming yesterday’s news. In addition white artists began to successfully cover his recordings, especially the whistling numbers.

Additional Resources

Brooks, Tim, Lost Sounds: Blacks and the Birth of the Recording Industry, 1890-1919 (University of Illinois Press, 2004), pp. 15-71, contains the most detailed story of Johnson’s life, including much original research.

Cylinder Preservation and Digitization Project, Department of Special Collections, Donald C. Davidson Library, University of California, Santa Barbara, accessible at http://cylinders.library.ucsb.edu/. This large and remarkable on-line collection has several Johnson titles available for listening or download.

Lost Sounds, Blacks and the Birth of the Recording Industry, 1891-1922 (CD: Archeophone ARCH 1005) contains eight Johnson titles for which there are surviving recordings.

Walsh, Jim, “Favorite Pioneer Recording Artists: George Washington Johnson,” Hobbies, Sept. 1944, 27.

Walsh, Jim, “Favorite Pioneer Recording Artists: In Justice to George Washington Johnson,” Hobbies, Jan. 1971, 37-39, 50, 91, Feb. 1971, 37, 39-40, 50, 92. The two pioneering articles by record historian Walsh, who corresponded with people who actually knew Johnson, were the only substantive biographical sketches published prior to Lost Sounds. While some of Walsh’s assumptions have been proven incorrect, the early articles add an invaluable human dimension to the story.

Acknowledgments and Notes

The “Whistling Coon” recording is on a North American wax blank, made in the early 1890s, and was probably the product of the New Jersey phonograph company or another company that did not identify its products. Courtesy of Ray Phillips.

The 1905 Edison cylinder of “The Laughing Song” is from the Cylinder Preservation and Digitization Project, UCSB.

Sources for quotes and information in the biography are in Lost Sounds, which contains extensive documentation.